9. Caches

Basics

Caches are a layer of memory hierarchy between registers and memory

They are not visible in application programming model

Buffer the references to main memory

Necessary in every g.p. computer due to growing performance gap between processor and memory

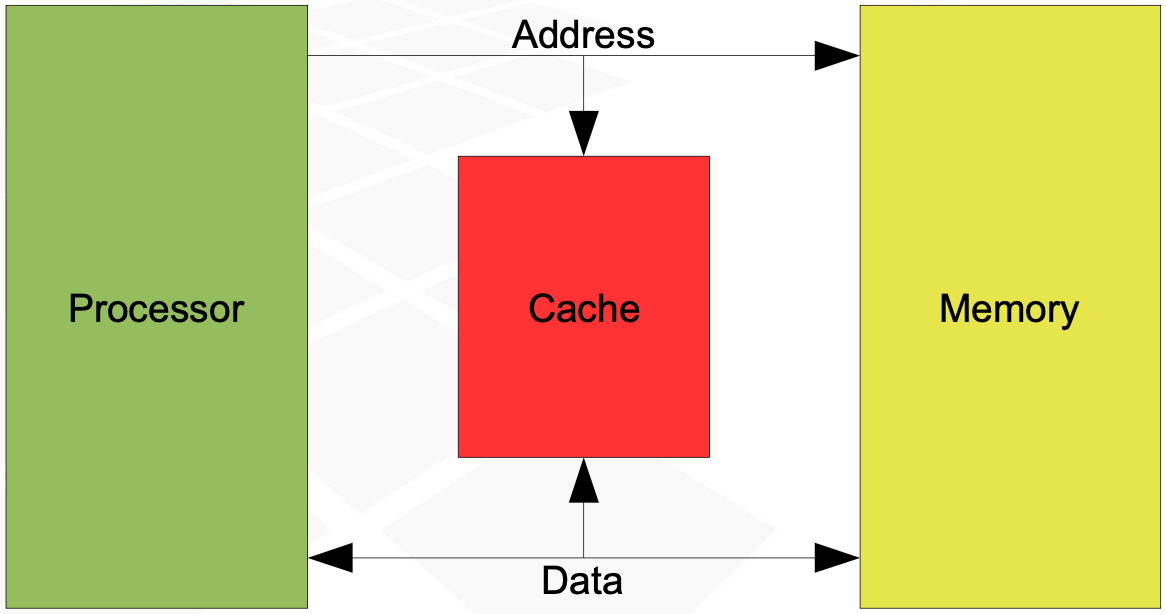

Cache operation

During every memory reference, the cache is checked for availability of data from a given address

Data not found - cache miss

data is fetched from memory and passed to processor

the data is also placed in the cache, together with its address

if cache is full - some item must be removed to make space for new data

during the next reference to the same address, data will be already in cache

Data found in cache - cache hit

data is fetched from the cache, no need to access memory

cache access is significantly faster than memory access

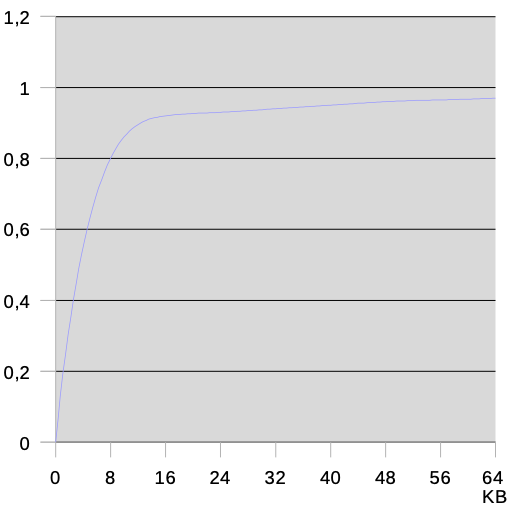

Locality of references

During a limited period of time, the processor references only a small range of memory addresses.

Plot shows the probability distribution of address access to during time

The range of references is limited

the set of addresses accessed by the processor in a limited period of time - working set

a relatively small buffer is capable of storing the content of a working set

The references are performed repetitively to the same addresses

The references to the consecutive addresses is very likely

good idea - while filling the buffer, fetch content of several consecutive addresses in advance

Fully associative cache

Most intuitive cache

Ineffective, difficult to implement - low capacity

Build using associative memory

no addressing needed for access

data is accessed based on association (matching) of data

memory response is data matched with input pattern

similar to a phone book

Characteristics

Every cell may store data from any address

all the cells must be searched during every access

Selection of victims (lines to replace upon miss) - LRU or random

Every CAM cell has its own tag comparator

With LRU algorithm, usually as soon as the size of working set exceeds cache capacity, all references result in misses

Cache design details

Data is stored in big units instead of bytes or words

units are called lines

usually

size-aligned

The LSB of address are used to select part of line

Direct mapped cache

Build using ordinary fast RAM and single equality comparator

fast and very simple to implement

high capacity thanks to low complexity

Simple but non-intuitive operation

LSB of address select a part of line

'middle', less significant part serves as the address of cache RAM

Each line contains address tag and data

Address tag contains the most significant part of address of data

Operation

During every access cycle one line is selected based on middle address bits

Cache hit - address tag matches the most significant bits of address sent by the processor

data is transferred from cache to the processor

Cache miss - selected line is replaced

MSB of address are stored in address tag

data is fetched from memory

Characteristics

Low cost, high capacity, high efficiency

No choice of replacement algorithm

data from given address may be stored only in one cache line

the cache cannot simultaneously store data from two addresses with identical middle parts (doesn't happen to often)

In case of dense working set (program loop, data table), the direct-mapped cache speeds up the references as long as the working set size is smaller then

Set-associative cache

Constructed from several direct-mapped caches (component caches called blocks)

Number of possible locations of data from a given address is equal to number of blocks

every cycle searches for a single line of every block

collection of selected lines is called a set

such set behaves like a tiny fully-associative cache

The number of blocks is called the cache associativity

the cache may be described as two-way or four-way

Set-associative cache may also be treated as connection of many small fully-associative caches

Operation

Design must guarantee that the data from a given address is never stored in more than one cache block

During miss, a line selected from the set is replaced

Set-associative characteristic is similar to direct-mapped one, but the problem of storing the data with identical middle part of address is solved

Cache organizations - summary

Most common cache architecture is set-associative

better characteristics than direct-mapped at marginally higher cost

Fully-associative caches are no longer used to store code and data

Hit ratio

Proportion of cache hits to total number of accesses in a given time period

Depends on

- cache capacity

- cache organization and replacement algorithm

- the program being executed

Meaningful measurement and comparing the hit ratio of different caches required defining the common workload set for testing

compiler, text editor, database, matrix calculations

Approximate relation between cache size and hit ratio

0.9 is achieved at about 8KiB

Above 0.9, architecture and replacement algorithm become significant factors

Average access time

Average access time of memory hierarchy composed of single cache and main memory

The cache connected to the processor must be designed in such way that it is able to supply data as fast as the processor requires - without any delays (assume

Conclusions

Intuitively high hit ratio does not translate to balanced cooperation between the processor and memory hierarchy

A single cache may compensate the difference in access time not exceeding 10x

To reduce average access time - improve miss response time

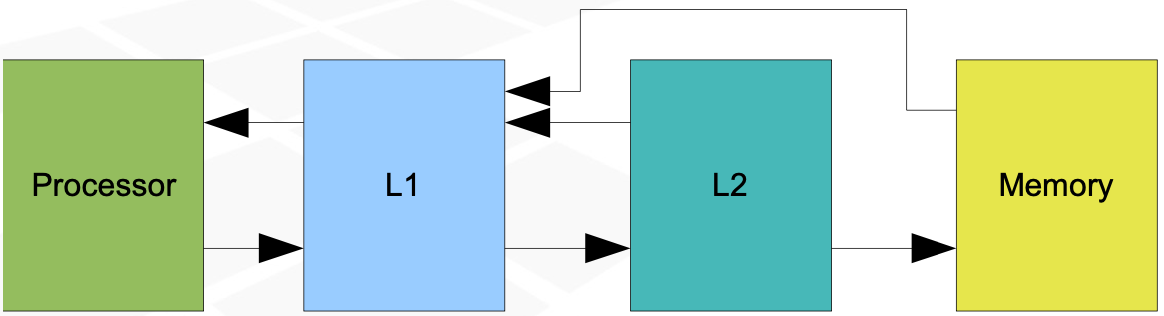

Multilevel caches

- L1 - (level 1) closest to the processor

- L2

- L3

Efficiency - 2 cache levels. Assume: - L1 - access time = 1, hit ratio 0.96

- L1 - access time = 5, hit ratio 0.99

- Main memory - access time 100 cycles

Average access time for memory - L2 cache:

Average access time for the whole memory hierarchy

The required speed of L1 cache is a limiting factor for its capacity and associativity

L2 may be slower than L1, so its associativity may be higher and it can be bigger

If L2 together with memory does not provide satisfactory average access time, L3 may be introduced

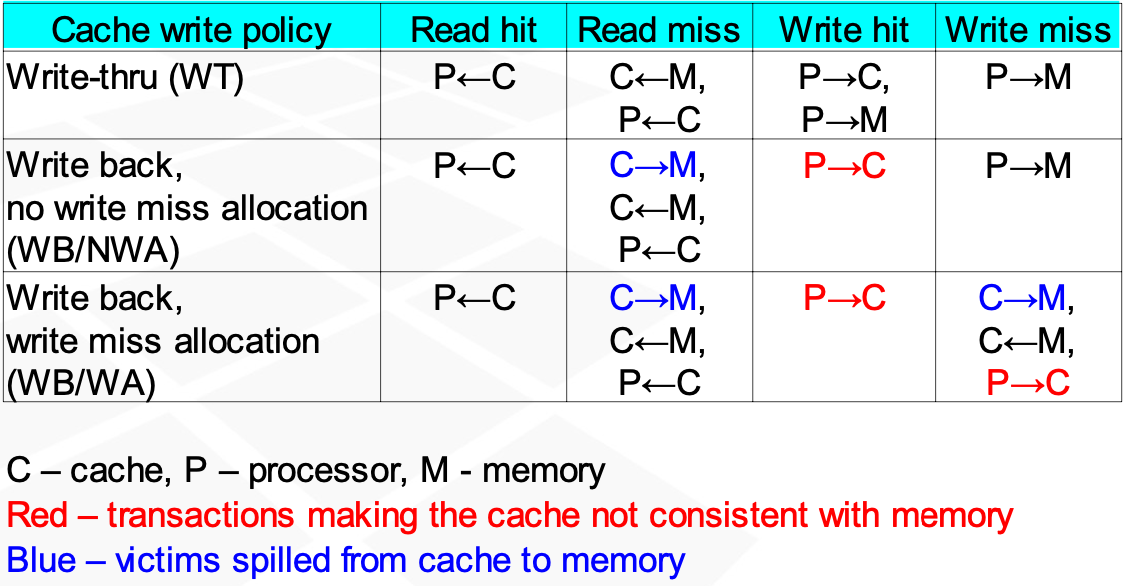

Cache operation during write cycles

To possible reactions of cache during write cycles

- Transparent write - data is always written to memory and if hit occurs - also to cache

- Write back - memory writes are deferred until absolutely necessary

Write back variants - No allocation during write miss

during write miss - data written only to memory

during write hit - only to cache - Allocation on write miss - always written only to cache

With write back, removing the line from cache may require writing it from cache to memory

Write policies

Inclusive caches

used until 2000

Data flow: Memory <-> L2 <-> L1 <-> Processor

Every object contained in an upper layer is also present in lower layers

Effective capacity of caches is equal to the capacity of the biggest cache

Exclusive caches

after 2000

Typically L2 is filled with objects removed from L1

L2 - victim cache

Data flow: Memory <-> L1 <-> Processor, L1 <-> L2 <-> Memory

L2 contains objects not present in L1

During L1 miss causing L2 hit, lines are exchanged

Effective total capacity is a sum of capacities of all levels

L2 capacity may equal to L1

L2 associativity should be higher than L1

L1 read miss handling

L2 hit:

- data exchanged between L1 and L2 - victim goes to L2 taking place of a line moved from L2 to L1

- no need to use a replacement algorithm for L2

L2 miss: - victim from L2 spilled to memory (if modified)

- victim from L1 evicted to L2

- new line read from memory to L1

Coherency of memory hierarchy

Memory hierarchy must be coherent

Every access to a give addr must yield the same data value, regardless of the layer being accessed

The coherency poses a problem when there is more than one path to the memory hierarchy:

- Harvard-Princeton processor with separate instruction and data cache

- Two processors with separate L1

- Processor with cache ad peripheral controller accessing the memory directly (not through cache)

Coherency doesn't require all contents of memory to be identical. Guarantee that every access will return the same value is enough.

Methods of achieving coherency

Invalidation of whole cache content upon detection of an external access to memory - used when caches were small

Selective invalidation of a line potentially storing data from address being accessed (until ~1990)

Software invalidation of a whole cache after external access

Selective change in line state after detecting the access to the address range stored in a line

Cache coherency protocols

State machine implemented for each line separately

Line states:

- M - modifies - line is valid and contains the only valid in the whole system (memory content is invalid)

- E - exclusive - valid and contains a valid copy of memory. no other cache contains the same line

- I - invalid

- S - shared - valid, there is more than one cache containing the line

- O - owned - valid, the same copy in several caches, other caches have state set to S, memory content invalid

Protocols - names originate from the set of states

MEI, MESI, MOESI

More states = less invalidations = better efficiency